Abstract

Studies on the breeding of vulnerable and endangered bird species are hindered by low numbers of individuals, inaccessible location of nests, unfavourable environmental conditions, and complex behavioural patterns. In addition, intraspecific variation may emerge only following long-term, systematic observations of little-known patterns and processes. Here, data collected over 30 years were used to determine growth model of hyacinth macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) chicks in the Pantanal biome of Brazil. During this period, the speed of growth and body mass of chicks varied widely. Four growth models were tested: logistic, Gompertz, Richards, and cubic polynomial. They were fitted using three biometric measurements: body mass, total length, and tail length. The best-fitting growth curves were identified using Akaike’s information criterion. The best models were the cubic polynomial for body mass, Richards for total length, and Gompertz for tail length. We confirmed the occurrence of dwarf individuals, whose body mass, total length, and tail length were 20%, 22%, and 70% smaller, respectively, than in the overall population. The dwarfs remain small in size after having fledged and are easily identified as adults. We discuss the importance of long-term studies to identify windows of opportunity for further research that will help in the conservation of endangered macaw species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the last 20 years, many species of Psittaciformes have faced an increasingly dire scenario, with an estimated 42% of them being endangered or near-threatened1. Berkunsky et al.2 identified agriculture, pet trade, logging, and human intrusions and disturbance among the various factors threatening neotropical parrots. Of the 86 known Brazilian parrot species, 17 are threatened nationwide3, two are extinct4,5, and 25 are threatened at a global level6.

The rapid and relentless loss of habitat, as well as the trade in wild animals have a particularly strong impact on parrots such as hyacinth macaws (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) characterised by a slow reproductive cycle7,8. The ongoing Arara Azul Project, which aims to improve the reproductive fitness of this species which is vulnerable to extinction3, has managed to boost the number of individuals, from 2500 in 1980 to 6000 in 20188,9,10,11. However, during 2019 and 2020, new threats have arisen, such as poisoning by agrochemicals12 and intense fires, which have substantially increased the mortality rate among nestlings and young individuals in the Pantanal region of Brazil13,14. Moreover, anthropogenic interventions, such as deforestation and fires, have drastically affected the population dynamics of the acuri palm (Scheelea phalerata), which constitutes the main food source for the hyacinth macaw during breeding15. During this period, marked differences have been observed in the size of some nestlings from the same clutch, with one nestling being smaller than the sibling and the population average.

The hyacinth macaw is an altricial species, which remains in the nest and is dependent on its parents for approximately three and a half months7. During this period, numerous factors can influence the growth of nestlings7,10,16,17. A number of factors have been found to directly affect the growth rate of Psittacidae, including environmental parameters (e.g. temperature and precipitation), food quality and availability, differences between the sexes, hatching-rank effects, clutch size, diseases, and ectoparasite infestations8,10,13,14,18,19,20,21,22. As a result, these factors generate intraspecific variations can lead to significant differences in growth rate, which in turn, can favourite adaptive processes such as a decreased competition between nestlings of the same clutch, or negative ones such as a reduced fertility10,16,18.

Given the many variables affecting Psittacidae fitness in the wild, growth models based on data collected from natural populations are tools which are important to help in the conservation of vulnerable species or those threatened with extinction. Growth models based on long-term datasets detail intraspecific variation that can aid in decision making regarding: (1) management of projects conducted in the field and aimed at invigorating wild populations; (2) rehabilitation and reintroduction to nature of specimens apprehended from illegal trade and the voluntary surrender of individuals rescued in natural environments; (3) management of pairs that occupy altered and fragmented habitats; and (4) raising specimens in captivity19,23,24. Additionally, growth curves can aid in the monitoring of populations that are managed in the field; these populations are a good indicator of the health of the species as well as of its environment25. Here, our objective was to analyse the growth of nestlings from a natural population of hyacinth macaws over 30 reproductive periods in the Brazilian Pantanal. To this end, different growth models were compared, and individual variations were fitted into the models to identify the most accurate ones.

Material and methods

Study area

During a period of 30 years (1991–2021) fieldwork were performed in the Pantanal region spanning the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Mato Grosso (16° 21′ S and 55° 58′ W) and in the last 15 years, in the Cerrado biome (Fig. 1), comprising a total area of approximately 3000 km2. Located in the states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Mato Grosso, but extending also into Bolivia and Paraguay, the Pantanal is the largest continental wetland area on the planet, covering approximately 140,000 km226,27. The climate of the Pantanal is classified as tropical wet according to the Köppen classification system and has an annual average temperature of 25 °C. Rainfall is more pronounced between November and April, resulting in two relatively well-defined seasons: a dry winter and a rainy summer season. According to Keuroghlian and Desbiez28, annual precipitation varies between 600 and 1700 mm (average of 1250 mm) in flooded areas, but is generally higher in upland areas, with an average of 1500 mm. The landscape of the Pantanal is a direct result of hydrological cycles. During the rainy season, up to 80% of the region is flooded, which makes access to this area difficult, and has discouraged human settlement. The complex hydrological network and large seasonal variations in water level have created a nutrient-rich environment that offers shelter and food to a diverse and abundant fauna29,30. Due to long periods of inundation, difficulty of access, and low population density, the Pantanal remains largely intact and is one of the most preserved biomes in Brazil, to the point of being designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and a World Heritage Site. However, in recent decades this biome have suffered with expansion and intensification of croplands, livestock, mining, and large government infrastructure projects31. These activities have greatly altered the Pantanal by accelerating deforestation and uncontrolled fires8,13,26,31,32, which has had negative repercussions on sensitive or threatened species, causing a loss in biodiversity14.

Source of political boundaries: IBGE (www.ibge.gov.br).

From 1991 to 2021, natural nests (n = 473, in blue) and installed artificial nests (n = 415, in red) were monitored in the Pantanal in the states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Mato Grosso, and more recently (last 15 years) in the Cerrado biome. This map was prepared independently with qgis v 3.10 software (www.qgis.org).

In order to develop the research, we received permission from the owners to enter the ranches in the Pantanal, follow the hyacinth macaws and monitor their nests. The fieldwork began before the formation of the Chico Mendes Institute of Biodiversity Conservation, ICMBio, in the year 2007, which currently authorizes and regulates scientific research in the country. At the time when this study begun, there was also not any need of a requirement to submit projects to ethics committees for studies on wildlife. NMRG (first author) was part of the hyacinth macaw conservation committees established by the Federal Government of Brazil since 1999, according to Ordinance No. 59 of the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Natural Resources, published on July 15, 1999.

Breeding characteristics

The hyacinth macaw is a species that is non migratory, monogamous, and highly specialized with respect to its feeding and nesting sites. Ninety-five percent of the nests are built in hollows in the manduvi tree (Sterculia apetala). There is strong competition among breeding hyacinth macaw pairs and other species for these hollows because only trees older than 60 years produce cavities large enough to be used by the macaws33. Approximately 75% of females lay two eggs, and of these there is a probability of 53% to lose one egg7,10. According to Guedes, for every 100 eggs laid, only 25% of them will survive until the chick leaves the nest10. The hyacinth macaw is an altricial species34, that is does not finish growing during the period it remains in the nest, that is, it only reaches the size of an adult after leaving the nest.

Field protocol

The process was initiated by observing a hyacinth macaw pair defending the nesting cavity in a tree. Once egg laying was documented, the nest was inspected regularly until the fledging of the chick, with day 1 defined as the day the egg hatched7,10. An OHAUS digital scale with a capacity of 2 kg was used to determine weight (g). Total length (mm) and medial tail feather length (mm) was measured with a metal ruler to the nearest 1 mm (Fig. 2A). To minimize potential observer bias, the measurements were conducted by the same person during the first 15 years and, thereafter, by two other researchers who rigorously adhered to a training protocol. Due to the location of the nests, difficulty to walk in the study area, and floods during certain periods of the year, the chicks were weighed at different day and time intervals. Additional weight variation came from variation of the quantity of food in the crop. The diameter of the crop was measured using a digital caliper to nearest 0.01 mm, and the volume (V) was calculated as V = 4*π*r3/3 (Fig. 2B). A model made of latex film and having the same volume as the crop when completely filled with Scheelea phalerata (Mart ex Spreng) Burret (Arecaceae) was constructed in the laboratory and the density (d = mass/volume) was calculated. In this way, the mass (M) of the crop was individually calculated as M = d*V and subtracted from the total body mass of the nestlings.

Hyacinth macaws are not sexually dimorphic, therefore, sex was identified by a blood sample of 0.1 ml from the brachial wing vein. The samples were kept at room temperature in absolute ethanol and sent to the Genetics and Molecular Evolution Laboratory at the Biology Institute of the University of São Paulo, Brazil. In the laboratory, DNA was extracted and PCR was run for sex identification following Miyaki et al.35,36. Due to logistical challenges in sending the samples, as well as to the remoteness of the nests and unfavorable weather conditions, not all the chicks were sexed (sex identification method details see Miyaki et al.36).

Of the 837 nestlings, not all individuals measured fledged; 395 died, mainly due to predators or other natural causes, such as infestation by ectoparasites. From more accessible nests, 42 eggs and from hatching (day 1) 30 nestlings (12 eggs failed) were monitored at the same time of day and with high-resolution temporal sampling (55 ± 11 days). The others 412 individuals were measured, from day 1, at the different time of day and with low-resolution temporal sampling (12 ± 7 days). Therefore, we included in this study only the individuals measured and weighed until they developed their full plumage. During the fieldwork we had already identified a group of nestling with metrics well below the other individuals, which we termed “dwarfs”. To identify and isolate the dwarfs from the total study population of 412 nestlings, we used field observations and cluster analysis (Euclidean distance and Ward methods) for the three metrics of body mass, total length and tail length. Cases of dwarfism were observed in the first and second nestlings for males and females. The total number of dwarfs observed was 31 individuals over 30 years of fieldwork; however, only 15 entered the analysis, which were those individuals that fledged. For a better flow of text, we termed the other individuals “normal-sized” birds.

Statistical analyses

We performed 89 measurements of the 15 fledged dwarfs and 1119 measurements of the 381 fledged normal-sized birds. Asymptotic models commonly used for the analysis of bird growth, including the Gompertz, Richards, and logistic models (sigmoidal curves), were evaluated, whereas a cubic polynomial model was applied to more complex growth curves. All models were fitted by minimising sum-of-squares of the residual errors and no parameters were constrained. In order to select the best model, we used the Akaike information criterion (AIC) values for sample sizes of > 30 individuals and AICc values for sample sizes of < 30 individuals, the F test, standard error of the residuals and selected the one that visually best fitted the data. Unlike the Akaike's criterion, which selects the model with highest probability to be correct37; the F Test defines the best model as the one with the lowest sum-of-squares. Using the best models for each of the morphological traits, we analysed changes to different growth curve parameters by including the upper asymptote (A), maximum growth rate (k), initial value (Y0) of the asymptotic curve for the Gompertz, Richards, and logistic models, and coefficient values (β0 = intercept, β1 = maximum relative growth rate, β2 = upper asymptote, β3 = weight loss begins) for the cubic polynomial model. We fitted the model to compare the first vs. second hatched nestlings and males vs. females. The analyses and figures were performed using GraphPad Prism Software, Inc. v. 838.

Results

Body mass

We weighed 42 eggs and obtained an average mass of 33.33 ± 3.99 g. Of these 30 normal-sized nestlings were monitored weekly at the same time of day. The average weight of the 30 nestlings was 23.00 ± 2.94 g/individual at day 1, 212.83 ± 32.62 g at day 15, 612.05 ± 30.47 g at day 30, 1188.74 ± 99.83 g at 60 days, and 1362.75 ± 47.10 g at 90 days. When the chicks left the nest after 107 days (average of 104 ± 4.4 days), their average weight was 1177.50 ± 105.47 g, while the maximum weight was 1550 g (average of 1240 ± 120 g). Chick development encompassed three phases: (1) nestling (0–25 days), during which chicks were completely dependent on their parents for maintaining body temperature, and weight gain was slow (Fig. 3A; nest with a normal-sized nestling and a dwarf one), (2) chick (26–77 days), a phase in which the mass gain was fast until maximum weight was reached (Fig. 3B = 44 and 45 days and Fig. 3C = 61 and 62 days), (3) youth (78–107 days), whereby weight was maintained up to 90–95 days (Fig. 3D), followed by weight loss concomitantly with the first attempts at flying and until permanently leaving the nest.

Development phases of the chicks: (A) nestling, 0–25 days, birds on picture are 17 and 18 days, respectively. Mass gain at this phase is slow, (B) chick, 26–77 days, birds on picture are 44 and 45 days, respectively, (C) chicks, birds on picture are 61 and 62 days, respectively. Geometric growth until maximum weight is attained, (D) juvenile, 78–107 days, birds on pictures are 104 and 105 days, respectively. Weight is maintained up to 90–95 days when weight loss begins with the first attempts of flying.

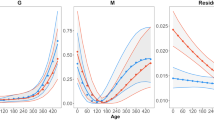

All models for normal-sized individual (n = 381) revealed similar R2 values for body mass with AIC indicating that the cubic polynomial performed best, probably because hyacinth macaw chicks lost weight during the final stages of development in the nest, and this loss required a more complex model (Table 1, Fig. 4A).

Growth curves fit of the four models tested in 412 nestlings of hyacinth macaws monitored over 30 years. The full black circles represent 381 individuals, and the empty squares represent the 15 dwarf individuals. (A) body mass, (B) total length, and (C) = tail length. Figures were produced using GraphPad Prism v. 8.

Field observations and cluster analysis showed that 15 individuals left the nest at a maximum of 126 days (average of 108 ± 15 days) with a maximum mass of 1000 g (average of 938 ± 63 g), which was approximately 22% less than that of the normal-sized individuals. This difference was reproduced by the models, with the asymptotes for the dwarfs reaching 77.4% of the Gompertz model, 72.2% of the logistic model, and 74.5% of the cubic polynomial model. Weight gain by the dwarfs was also lower compared to normal-sized birds, reaching 68.5% of the Gompertz model, 23.5% of the Richards model, 75.6% of the logistic model, and 51.6% of the cubic polynomial model (Table 1). When comparing the results generated with the Richards model, the differences were less pronounced, but the difference between the two groups remained significant (Table 1). Therefore, the dwarfs gained less weight (A) and did so more slowly (k). They reached maximum weight only when they were ready to leave the nest without any weight loss prior to nest abandonment, which resulted in the lowest AIC for the Gompertz model (Table 1, Fig. 4A).

Total length

The average length and width of a hyacinth macaw egg (n = 42) was 47.32 ± 0.96 mm and 36.59 ± 0.93 mm, respectively. The 30 chicks monitored with high-resolution temporal measured on average 77.00 ± 1.00 mm and had a total length of 147.00 ± 11.64 mm at day 15, 249.00 ± 13.46 mm at day 30, 417.12 ± 7.52 mm at day 60, and 591.09 ± 53.81 mm at day 90. When leaving the nest, the average total length was 677.25 ± 12.91 mm. Concerning the 381 normal-sized individuals, the Richards and cubic polynomial models performed best in describing total length, i.e. these models had the lowest AIC (Table 2). Both models showed a predominance of the linear phase, with k = 7.79 (Richards) and β1 = 5.26 (cubic polynomial, Table 2; Fig. 4B). When total length curves were compared, significant differences were observed between the normal-sized individuals and the dwarfs. The latter not described well by the Richards model, with large standard error values denoting uncertainty in the model’s fit. The Gompertz and logistic models exhibited the best performance based on AIC, and, despite the low value of the asymptote, the dwarfs maintained the same rate of growth (k) compare to total length normal-sized birds in the logistic model (Table 2).

Tail length

In general, the tail feathers grew rather rapidly. The first pin feathers appeared after 25–31 days and, by the time the birds left the nest, the tail feathers accounted for approximately 50% of the total length of the tail. Although the Richards model was numerically better and Gompertz was the second best model for the 381 normal-sized individuals (Table 3; Fig. 4C). The tail feathers of 15 dwarf birds were best described by a Gompertz model, which resulted in dwarfs with total length, on average, 70% smaller and asymptote 84% higher for the dwarfs than the normal-sized chicks. This indicates either an overestimation or that the dwarfs left the nest during the linear growth phase before reaching the asymptote. In the Gompertz model, the growth rate (k) was 30% slower, and explained 93.9% of the variation observed in these individuals. The other models did not fit the tail growth data as in the case of the Richards and Logistic models, resulting in wide confidence intervals (CI > 95%) which results in model instability.

Differences among nestlings

We used the cubic polynomial and Gompertz models to compare the first (n = 294) and second hatched (n = 87) chicks as well as males (n = 148) and females (n = 226), all of which were normal-sized (Fig. 5A–C). This analysis revealed differences between model parameters (Table 4). Weight gain was slower for the second chick (β1 = 13.51) and 42% faster for the first chick during the linear phase (β1 = 23.29), this result reflected a significant difference in the fitting of the curves. Nevertheless, the goodness of fit was significantly different, being male model better than female. The values obtained for the asymptote and rate of increase in total length for the first and second chicks were statistically different. For the mass increment, the variation to model parameters was not so clear, with β0, β1, β3 without differences and for β1 the difference was significant between males and females. In addition, the AIC values indicated that the curve fitted better to the male chicks dataset. Total growth between sex not was statistically different, including the curve fit for the two datasets, confirming the lack of sexual dimorphism in total length (Table 4; Fig. 5B). However, there were differences between tail size, with tail size 24% greater in males than in females (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

The total period of development of the hyacinth macaw normal-sized chicks lasted 107 days with an average final body mass of 1177.5 ± 105.4 g. Given that this is the largest flying parrot, hole-nesting, feature small clutches, and a specialized diet, is expected to have slower growth rate than for other species34, such as Calyptorhynchus latirostris39, Myiopsitta monachus40, Ara ararauna41, Forpus passerinus42, Amazona autumnalis, Amazona oratrix, Amazona viridigenalis43, Primolius maracana44, Cyanoliseus patagonus20, Amazona aestiva45, and Ara macao46.

The AIC values showed that the choice of model depended on the growth metrics analyzed. Accordingly, the best models for normal-sized individuals were the cubic polynomial for body mass, Richards and cubic polynomial for total length, and Gompertz for tail length. Tjørve and Tjørve47 comment that species with growth patterns that demand more complex growth models are quite uncommon. The post-natal growth rate results in hyacinth macaws to reach adult body mass late in the growth cycle, that is, after abandoning the nest but while still needing parental care48,49,50. This phenomenon is observed also in species whose young reach peak body mass before starting flight exercises, which results in weight loss while still in the nest, mass recession, and the attainment of adult body mass only after leaving the nest51,52. In these instances, the Gompertz, Richards, and logistic growth curves, can yield unrealistic values. This was the case for the hyacinth macaw, whose maximum weight was reached at approximately 80 days, but then declined before finally attaining adult weight after fledging. These behaviour help explain why the cubic polynomial model is the best fit for body mass; whereas the sigmoidal models is the best fit for total length and tail length, as its function better reflects the continuous growth of tail feathers until adult size is attained.

Our results corroborate the field observations and reveal significant intraspecific differences among growth of hyacinth macaw chicks. Many studies report the existence of intraspecific variation in growth rates, most of which is explained by the availability of food resources, physiological differences, low reproductive performance of parents, phenotypic plasticity, natural and anthropic environmental factors17,20,53. However, intraspecific variation related to growth rates can vary between species, principally between those that are altricial, wild, and display slow growth rates, which makes them more prone to suffer from environmental changes and predation16,34,54,55. These sources of variation, coupled with the large number of individuals sampled over a long period, had a strong influence on how the growth models fitted each biometric trait. For example, the wide range of initial values and inflection points determines more or less elongated curves and modifies the maximum asymptote, which in turn leads to individual body mass and total length variation and a growth rate slower or faster increase17,47. These sources of variation in birds are observed mainly as a function of the time it takes to hatch, sex, sampling year, and locality16,19,20,54.

Despite phenotypic variations and changes affecting the shape of the growth curve, we did not find studies describing different growth patterns within the same species, clutch, or locality in natural populations. Our results indicate that there are chicks observed in the natural habitat, which were much smaller than the rest of the evaluated chicks, thus confirming the supposed existence of dwarfs. In this dwarf group, body mass increment and overall weight gain were 54% (average of all models) below normal-sized and there was no weight loss before the birds left the nest. According to Ricklefs16, growth traits can exhibit as much as 20% intraspecific variation with respect to geographic location and time of the nesting season. In this context, all models revealed differences of less than 20% for the dwarfs, being approximately 22%, 27% and 70% to mass, total length, and tail length respectively. It is important to emphasize that these individuals will not attain the same adult size as the rest of the chicks and will always be easily recognizable in the field. Additionally, these individuals form couples with larger adults of both sexes and are not limited by low reproductive success56. These cases were identified due to the long-term design of this study, which involved 30 years of morphometric monitoring of free-living hyacinth macaws. As they represented only 8.1% of all measured individuals and that fledged, it would have been unlikely to identify dwarf individuals in short-term studies.

The growth models for the hyacinth macaw developed in this study demonstrate the specific and complex biological and behavioural characteristics of this species. Intraspecific variation, such as that between males and females and the first and second hatched nestlings, was observed. However, these differences can hardly be recognized by an observer in the field. On the other hand, dwarf animals can easily be recognized by an observer in the field, although most of the time they are confused with a young individual. Perhaps for this reason dwarfs have rarely been described in natural populations. Our finding opens opportunities to examine whether this species may take advantage of intraspecific variability to overcome difficulties such as the recent fires that reduced food availability. We believe that these results can also support the management of other Psittaciformes. For example, carrying out projects that identify the health of individuals which do not reach the maximum standard of growth, which are mainly those coming from voluntary surrender or are rescued. In addition, our results reaffirm the importance of long-term studies, especially for species that are vulnerable and threatened with extinction.

Data availability

The data is available to any personnel who wish to analyze any pattern or hypothesis. As long as you take into account the authorship of the database.

References

BirdLife International. Red List Update: Parrots of the Americas in Peril. https://www.birdlife.org/news/2021/02/08/red-list-update-parrots-of-the-americas-in-peril/ (2020).

Berkunsky, I. et al. Current threats faced by Neotropical parrot populations. Biol. Cons. 214, 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.08.016 (2017).

ICMBIO—Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (Org.). Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção: Volume III-Aves 709. https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/comunicacao/publicacoes/publicacoes-diversas/livro_vermelho_2018_vol3.pdf (Ministério do Meio Ambiente, 2018).

CBRO—Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos. Listas das Aves do Brasil. 11th ed. http://www.cbro.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/avesbrasil_2014jan1.pdf (CBRO, 2014).

Pacheco, J. F. et al. Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee—second edition. Ornithol. Res. 29(2), 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43388-021-00058-x (2021).

IUCN—International Union for Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species www.iucnredlist.org (2018).

Guedes, N. M. R. Biologia reprodutiva da arara azul (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) no Pantanal—MS, Brasil. (Dissertação de Mestrado Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo (1993).

Guedes, N. M. R. et al. Technical Report Assessing the Impact of Fire on Blue Macaws, Pantanal, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, p 13, Campo Grande, Instituto Arara Azul (2019).

Guedes, N. M. R. Araras azuis: 15 anos de estudos no Pantanal. In Paper presented at IV Simpósio Sobre Recursos Naturais e Sócio-Econômicos do Pantanal, Corumbá: Embrapa Pantanal (2004).

Guedes, N. M. R. Sucesso reprodutivo, mortalidade e crescimento de filhotes de araras azuis Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus (Aves, Psittacidae), no Pantanal, Brasil (Tese de doutorado Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu, 2009)

Guedes, N. M. R. & Harper, L. H. Hyacinth macaws in the Pantanal. In The Large Macaws (eds Abramson, J. et al.) 394–421 (Raintree Publications, 1995).

Vicente, E. C. & Guedes, N. M. Organophosphate poisoning of Hyacinth Macaws in the Southern Pantanal, Brazil. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84228-3 (2021).

Guedes, N. M. R. et al. Assessment of fire impact on Hyacinth Macaws in Perigara, Pantanal—MT, Brazil, p 35, Campo Grande, Instituto Arara Azul (2020).

Guedes, N. M. R. et al. Macaws survive fires and provide hope for resilience—Stubborn survivors. Pantanal Sci. Mag. 6, 36–41 (2021).

Oliveira, M. D. R. et al. Lack of protected areas and future habitat loss threaten the Hyacinth Macaw Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus and its main food and nesting resources. Ibis 163, 1217–1234 (2021).

Ricklefs, R. E. Patterns of growth in birds. Ibis 110, 419–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1968.tb00058.x (1968).

Gebhardt-Henrich, S. & Richner, H. Causes of growth variation and its consequences for fitness. Oxford Ornithol. Ser. 8, 324–339 (1998).

Masello, J. F. & Quillfeldt, P. Body size, body condition and ornamental feathers of Burrowing Parrots: Variation between years and sexes, assortative mating and influences on breeding success. Emu Austral Ornithol. 103, 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1071/MU02036 (2003).

Renton, K. Influence of environmental variability on the growth of Lilac-crowned Parrot nestlings. Ibis 144, 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1474-919X.2002.00015.x (2002).

Masello, J. F. & Quillfeldt, P. Chick growth and breeding success of the Burrowing Parrot. Condor 104, 574–586. https://doi.org/10.1650/0010-5422 (2002).

Pacheco, M. A., Beissinger, S. R. & Bosque, C. Why grow slowly in a dangerous place? Postnatal growth, thermoregulation, and energetics of nestling green-rumped parrotlets (Forpus passerinus). Auk 127, 558–570. https://doi.org/10.1525/auk.2009.09190 (2010).

Vigo, G., Williams, M. & Brightsmith, D. J. Growth of Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao) chicks in southeastern Peru. Neotrop. Ornithol. 22, 143–153 (2011).

Lyon, J. P. et al. Reintroduction success of threatened Australian trout cod (Maccullochella macquariensis) based on growth and reproduction. Mar. Freshw. Res. 63, 598–605. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF12034 (2012).

Vigo-Trauco, G., Garcia-Anleu, R. & Brightsmith, D. J. Increasing survival of wild macaw chicks using foster parents and supplemental feeding. Diversity 13, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13030121 (2021).

Tellería, J. L., De La Hera, I. & Perez-Tris, J. Morphological variation as a tool for monitoring bird populations: A review. Ardeola 60, 191–224. https://doi.org/10.13157/arla.60.2.2013.191 (2013).

Silva, J. S. V. Elementos fisiográficos para delimitação do ecossistema Pantanal: Discussão e proposta. Oecol. Brasil. 1, 349–458. https://doi.org/10.4257/OECO.1995.0101.22 (1995).

Silva, J. S. V. & Abdon, M. M. Delimitação do Pantanal Brasileiro e suas Sub-Regiões. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 33, 1703–1711 (1998).

Keuroghlian, A., Eaton, D. & Desbiez, A. L. J. The response of a landscape species, white-lipped peccaries, to seasonal resource fluctuations in a tropical wetland, the Brazilian Pantanal. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 1, 87–97 (2009).

Donatelli, R. J., Posso, S. R. & Toledo, M. C. B. D. Distribution, composition and seasonality of aquatic birds in the Nhecolândia sub-region of South Pantanal, Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 74, 844–853 (2014).

Donatelli, R. J. et al. Temporal and spatial variation of richness and abundance of the community of birds in the Pantanal wetlands of Nhecolândia (Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil). Rev. Biol. Trop. 65, 1358–1380 (2017).

Tomas, W. M. et al. Sustainability agenda for the Pantanal Wetland: Perspectives on a collaborative interface for science, policy, and decision-making. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 12, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082919872634 (2019).

Harris, M. B. et al. Safeguarding the Pantanal wetlands: Threats and conservation initiatives. Conserv. Biol. 19, 714–720. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00708.x (2005).

Santos Júnior, A. D., Aspectos populacionais de Sterculia apetala (Jacq.) Karst (Sterculiaceae) como subsídios ao plano de conservação da arara-azul no Sul do Pantanal, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. (2006). https://repositorio.ufms.br/handle/123456789/521.

Ricklefs, R. E. The optimization of growth rate in altricial birds. Ecology 65, 1602–1616 (1984).

Bruford, M. W., Hanotte, O., Brookfield, J. F. Y. & Burke, T. Single-locus and multilocus DNA fingerprinting. In Molecular Genetic Analysis of Populations: A Practical Approach (ed. Hoelzel, A. R.) 225–269 (Oxford University Press, 1992).

Miyaki, C. Y. et al. Sex identification of parrots, toucans, and curassows by PCR: Perspectives for wild and captive population studies. Zoo Biol. 17(5), 415–423 (1998).

Cavanaugh, J. E. & Neath, A. A. The Akaike information criterion: Background, derivation, properties, application, interpretation, and refinements. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 11, 1460. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.1460 (2019).

Motulsky H. J. GraphPad curve fitting guide. 2021. http://www.graphpad.com/guides/prism/7/curve-fitting/index.htm. Accessed 18 September.

Saunders, D. A., Smith, G. T. & Rowley, I. The availability and dimensions of tree hollows that provide nest sites for cockatoos (Psittaciformes) in Western Australia. Wildl. Res. 9, 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR9820541 (1982).

Navarro, J. L. & Bucher, E. H. Growth of monk parakeets. Wilson Bull. 102, 520–525 (1990).

Murtaugh, P. A. Performance of several variable-selection methods applied to real ecological data. Ecol. Lett. 12, 1061–1068 (2009).

Waltman, J. R. & Beissinger, S. R. Breeding behavior of the Green-rumped Parrotlet. Wilson Bull. 104, 65–84 (1992).

Enkerlin-Hoeflich, E. C., Packard, J. M. & González-Elizondo, J. J. Safe field techniques for nest inspections and nestling crop sampling of parrots. J. Field Ornithol. 70, 8–17 (1999).

Barros, Y. de M. Biologia comportamental de Propyrrhura maracana (Aves, Psittacidae): Fundamentos para conservação in situ de Cyanopsitta spixii (Aves, Psittacidae) na Caatinga. (Tese de Doutorado Universidade Estadual de São Paulo, Rio Claro, 2001).

Seixas, G. H. F. & Mourão, G. M. Growth of nestlings of the BlueFronted Amazon (Amazona aestiva) raised in the wild or in captivity. Ornitol. Neotrop. 14, 295–305 (2003).

Vigo-Trauco, G. Crecimiento de pichones de Guacamayo Escarlata, Ara macao (Linneus: 1758) en la Reserva Nacional Tambopata-Madre de Dios-Peru (Tese Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, 2007).

Tjørve, K. M. & Tjørve, E. The use of Gompertz models in growth analyses, and new Gompertz-model approach: An addition to the Unified-Richards family. PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178691 (2017).

Reed, J. M. The role of behavior in recent avian extinctions and endangerments. Conserv. Biol. 13, 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.013002232.x (1999).

Tjørve, K. M., Underhill, L. G. & Visser, G. H. Energetics of growth in semi-precocial shorebird chicks in a warm environment: The African black oystercatcher, Haematopus moquini. Zoology 110, 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zool.2007.01.002 (2007).

Tjørve, K. M., Underhill, L. G. & Visser, G. H. The energetic implications of precocial development for three shorebird species breeding in a warm environment. Ibis 150, 125–138 (2008).

Ricklefs, R. E. Weight recession in nestling birds. Auk 85, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/4083621 (1968).

Huin, N. & Prince, P. A. Chick growth in albatrosses: Curve fitting with a twist. J. Avian Biol. 31, 418–425. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-048X.2000.310318.x (2000).

Corsini, M. et al. Growing in the city: Urban evolutionary ecology of avian growth rates. Evol. Appl. 14, 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.13081 (2020).

Barbosa, L. T. Avaliação do sucesso reprodutivo da arara-canindé (Ara ararauna—Psittacidae) e o desenvolvimento urbano de Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul (Dissertação de mestrado Universidade Anhanguera Uniderp, Campo Grande, 2015).

Giraldo-Deck, L. M. et al. Development of intraspecific size variation in black coucals, white-browed coucals and ruffs from hatching to fledging. J. Avian Biol. 51, e02440. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.02440 (2020).

Guedes et al. Annual Technical Report from the Instituto Arara Azul., Pantanal-MS, Brazil. 35p, Campo Grande, Instituto Arara Azul (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank the following assistants or interns for their contributions to the fieldwork: Carlos Cézar Corrêa, Neliane R. Corrêa, Joilson de Barros, Vanessa Bernardo, Marcos Ferramosca, Douglas Kajiwara, Rodrigo Lott, Adriana Marques, Patrícia Faria, Flávia Presti, Flávia Vargas, Douglas Fernandes, Andrea Macieira, Erica Pacífico, Luiz Tadeu Braga, Monalyssa Camandaroba, Juliana Rechetelo, Larissa Tinoco, Karlla Barbosa, Thiago Filadelfo, Iara Niero, Daphne Nardi, Kefany Ramalho, Kalyenny Costa, Sophia Guedes, Marina Marchesi, Lucas Rocha, Gabriela Corrêa, Edson Diniz, Luciana Ferreira, Sabrina Appel, Isabela Nogueira, Julia Satyro, Everson Freitas, Ana Cecília Lourenço, Luiz Dervalho, Rodrigo de Oliveira. The authors also thank the members of the Communication Department of the Arara Azul Institute: Eveline Castanho, Eliza Mense, Elisiane Mascarenhas and Cynthia Mazzi. We also thank Uniderp for technical support, Refuge Ecological Caiman and Embrapa/CPAP for logistical support, and for financial support we thank the Toyota Brazil Foundation, Zoo Zurich-WCS, WWF, Boticário and Parrots International. We thank the anonymous reviewers, Troy Bendini and especially Bettina Wachter for contributions that greatly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.M.R.G. conceived, designed and developed the project with field data collection in the first 15 years; N.M.R.G., F.M.F. and G.F.S. collected field data in the last 15 years; N.M.R.G. and M.C.B.T. did the experimental part and tabulation of the data; M.C.B.T. did the statistical analysis and graphics; N.M.R.G., M.C.B.T. and R.J.D. analysed the results and wrote the main text of the manuscript, and the authors revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guedes, N.M.R., Toledo, M.C.B., Fontoura, F.M. et al. Growth model analysis of wild hyacinth macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) nestlings based on long-term monitoring in the Brazilian Pantanal. Sci Rep 12, 15382 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19677-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19677-5

This article is cited by

-

First record of free-living hyacinth macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) eggs hatching using camera traps in southern Pantanal, Brazil

Ornithology Research (2024)

-

Wildfires Jeopardise Habitats of Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus), a Flagship Species for the Conservation of the Brazilian Pantanal

Wetlands (2023)